Episode 01

The New Atlantis: Charter Cities

Archived audio: I’m at the airport in Lagos and electricity just went off for, this is five minutes and there’s still no lights at the airport—the international airport, Lagos.

Wooo! Finally we got lights.

Tamara Winter: Lagos, Nigeria is one of the largest cities in the world. It’s home to over 14 million people and one of Africa’s main economic hubs. It’s the most populous city in the country with Africa’s largest GDP. However in Lagos, even basic services are unreliable.

Archived audio: Everything comes to life when there’s light. When there’s no light you can literally feel handicapped.

Tamara Winter: This isn’t a new problem in Lagos. An unstable power grid and political corruption make providing everyday utilities—like electricity—a struggle. In 2016, The Guardian reported on a neighborhood that went without power for five years because its residents refused to pay bribes.

These kinds of challenges are not unique to Lagos or even to Nigeria. Across the developing world—from Jakarta to Kinshasa—cities are growing rapidly. New residents are pouring into cities that have neither the infrastructure nor the institutions to adequately serve them.

In his 2005 book Planet of Slums urban theorist Mike Davis chronicled the rise of million-person cities in the developing world. He described the lives of the more than one billion people who live in the world’s slums.

Booming populations of these fast-growing cities find themselves in harsh living conditions. Flooded streets. Poor ventilation. Little to no waste clearance. And few basic services.

The absence of infrastructure makes life dangerous.

Lack of access to sanitation and healthcare are directly responsible for high infant and maternal mortality.

Communicable diseases—that have become a thing of the past elsewhere—run rampant.

Despite these challenges, people across the developing world are seeking out the economic opportunities that cities provide.

So, is there another way? Another avenue for people in search of a better life to access not only economic opportunities, but also stable governance and reliable institutions.

In this episode, we’ll be looking at one possible solution: charter cities. Built—sometimes almost from scratch—in developing countries. These developments are outside-the-box infrastructure. Rather than reforming or building on existing cities they are new constructions often with their own economic regulations and laws. Privately backed. And focused on bringing economic growth to emerging economies. Supporters see them as a way to theoretically seed the ground for more stable institutions and improved governance.

Hello and welcome to the first episode of Beneath the Surface, a podcast series from Stripe Press exploring new ideas and big questions in the world of infrastructure. I’m your host, Tamara Winter.

It’s not an accident that the first episode begins in Nigeria. That’s where I was born. My family moved to the United States when I was just two months old. But growing up in Texas I often wondered: what if instead of being raised in Dallas, I grew up in Lagos, like the majority of my family? That question is part of why I’ve always been so fascinated by questions about development and specifically, about Africa’s trajectory. It’s part of my story.

I’m also no stranger to the world of new cities. I used to work at the Charter Cities Institute. We’ll actually hear from the institute’s founder Mark Lutter a little later in this episode. The Institute, based in Washington D.C. is a non-profit that’s working to build the ecosystem for charter cities by developing institutional frameworks that can guide their creation.

Now, before we get into the nitty gritty, I want to be really clear about some of the words we’re using in this episode. You’ve already heard me say ‘new cities’ and ‘charter cities.’ There’s a pretty broad ecosystem of new city projects. So when we’re talking about the whole landscape, I’ll use the term ‘new cities’—charter cities are just one part of that world, the part most focused on leveraging the creation of new cities for global development.

So, what are charter cities and where did the idea for them come from in the first place?

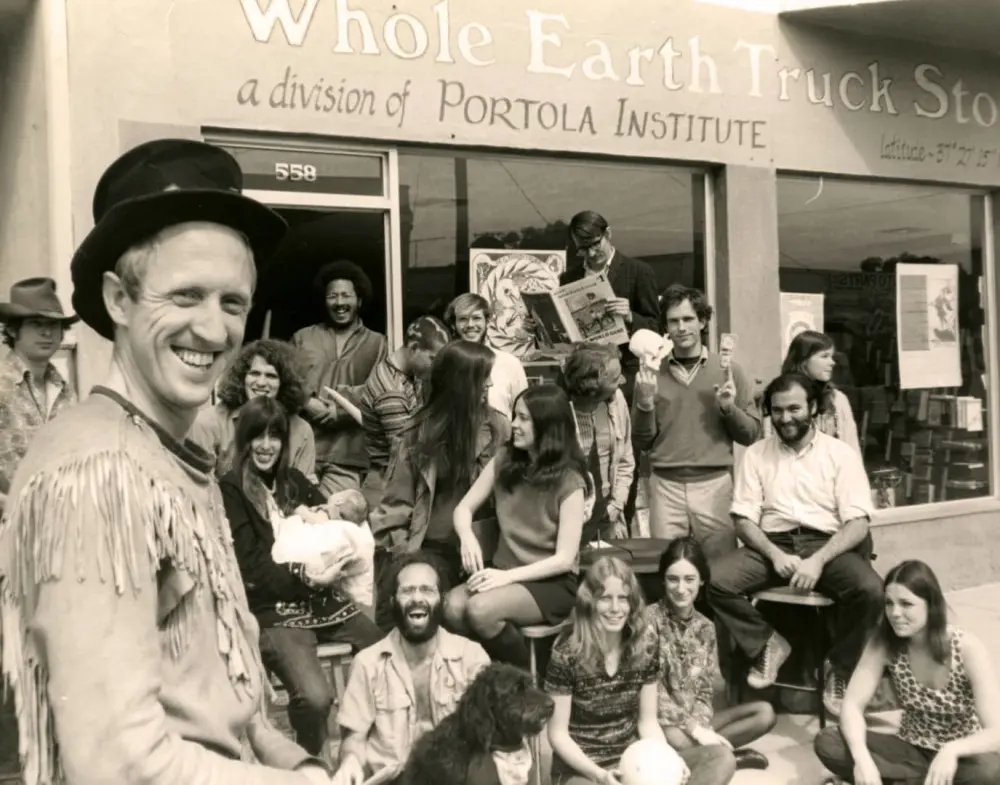

If you spend any amount of time talking to folks about new cities there’s one name that will keep popping up.

Person 1: Paul Romer

Person 2: Paul Romer

Person 3: Professor Paul Romer

Tamara Winter: Paul. Romer.

He’s not a household name, but he’s been one of the most influential economists in the world for the last 20 years. He’s a former Chief Economist at the World Bank and in 2018 he even won the Nobel Prize.

Archived audio: Dear Professor Romer...the tools you have developed broaden the scope of economic analysis...I now ask you to receive your prizes from his Majesty the King.

Tamara Winter: He’s a big deal—if you’re an economist. But that’s not why all these people mention his name. In 2009, he gave a TED Talk. Now this might not seem that exciting—an economist giving a 20 minute lecture about his new idea. In fact, if you watch the talk—it’s on YouTube—you might not walk away inspired to start a city of your own.

Romer walks on stage his hair more salt than pepper and close-cropped, wearing blue jeans and a dark suit jacket over a button down shirt.

He paces back and forth while he talks, a clicker in his right hand occasionally changing slides behind him. His voice is steady, not monotonous, but not an orator’s.

The talk has been posted on YouTube for just over 12 years and has only a little more than 150,000 views.

However, for many who saw this talk back in 2009, who were captivated by Romer’s ideas, it was an a-ha moment. Like when the Beatles first went on the Ed Sullivan show.

Back in 1964 a generation of young music lovers saw four guys from Liverpool playing music on their TV and thought to themselves: maybe my friends and I can do that.

Inspired by Romer’s talk, many entrepreneurs began wondering the same kind of thing—what if they could build charter cities too.

So—Romer’s idea. Charter cities. New cosmopolitan growth centers that would promote economic development and connect developing countries to the rest of the global economy.

Romer’s proposed cities would be more than special economic zones—areas with different economic regulations—they would also be special governance zones. Places where different laws would allow for faster economic growth thanks to better institutions.

Romer imagined cities located in developing countries administered by the governments of developed countries.

Now, more than 12 years after Romer’s talk, if you ask some of the people most involved with the movement what charter cities are, and what purposes they serve, you’ll get pretty different answers.

Patri Friedman: I think of a charter city as a special jurisdiction that is a geographic area that has different laws and institutions from the rest of the country. And the amount of difference has to be more than a special economic zone which typically just has some tax breaks, tariff breaks, a small number of legal changes.

Tamara Winter: That was Patri Friedman. He runs Pronomos Capital, a venture capital firm which invests in new city projects. Their slogan: Better laws. Better lives. Oh, and if you caught that his last name is Friedman. Yeah, he’s the grandson of legendary economist Milton Friedman.

He got his start in the world of new cities when he founded the Seasteading Institute. A non-profit that worked to establish autonomous communities on free-floating platforms stationed in international waters. Friedman’s interest in new cities came from his analysis of governance as a kind of product that should be subject to updates.

Patri Friedman: Why do our cellphones get better every year and our governments maybe occasionally get better, maybe sometimes degrade and what I realized is that if you throw away all the morality and philosophy and say, “Okay this is an industry”, what characteristics does it have?

Tamara Winter: Mark Lutter, the founder and executive director of the Charter Cities Institute has a slightly more technical definition of what constitutes a charter city.

Mark Lutter: So a charter city is a new city development: a new city with better laws. Paul Romer, for example, was advocating that high-income countries such as Canada act as a guarantor in a low-income country such as Honduras. And the Charter Cities Institute moved away from this, I guess, this idea, this definition, arguing for a public-private partnership.

Tamara Winter: Lutter founded the Charter Cities Institute just one year after finishing his PhD in economics. In his view, charter city developments, if and when successful, will have long term positive impacts beyond the cities themselves.

Mark Lutter: Charter cities have primarily been focused on emerging markets, creating a space with new institutions. So this would be going to places like Nigeria, Zambia, Honduras and creating new city developments that allowed for people to be able to hire more easily to, resolve disputes more easily to pay taxes, to register a business, having a government that’s effective at providing public goods, and this would allow for sustained economic development over time.

Tamara Winter: The Institute’s website lists some of the existing cities that they see as examples of this model—jurisdictions that improved their governance and, as a result, their economic output.

Dubai. Singapore. Shenzhen. Hong Kong.

These cities have all experienced astronomical growth in relatively short periods of time. The Charter Cities Institute’s website has a slideshow with before and after images of each city and information about their growth.

The images that accompany these numbers are just as striking. Shenzhen in 1980 is a pastoral scene of green fields, rolling hills, and distant mountains—home to about 300,000 people. But by 2017, it is all sleek skyscrapers and glowing lights—a metropolis with a population to rival New York City. Oh, and the average yearly income increased over 10,000 percent, too.

Browsing these figures. Listening to Friedman and Lutter. And hearing Romer’s optimism echoing from 2009, it’s easy to understand why so many people are so dedicated to promoting the idea of new cities.

But what do these numbers really mean? Who are these cities being built by? And maybe more importantly, who are they being built for?

I first met Mwiya Musokotwane on a trip to a remote island in Zambia. I was there as part of my work for the Charter Cities Institute.

Mwiya’s a stoic, physically imposing guy, well over six feet tall. I’ve known him for a while now and he’s basically got two speeds: full suit and sweatsuit. He’s either in board rooms, meeting with elected officials, and giving presentations, or he’s at home being a doting dad, the kind who keeps a lot of pictures of his daughter in his pocket—and on his Instagram.

He’s the co-managing partner, along with his father, of Thebe Investment Management and the founder of Nkwashi, a new charter city project in Zambia.

Mwiya Musokotwane: Zambia, it’s kind of like the junction point between Central Africa, Eastern Africa, and Southern Africa, and like South Western Africa also. Lake Tanganyika which is the world’s second longest and second largest lake by volume is partly in Zambia. The source of the largest river in southern Africa is in Zambia so it’s at the confluence of these interesting things.

Tamara Winter: Zambia’s natural resources, especially copper, made it a target for colonization. But Zambia had a distinctly different experience than its neighbors.

Mwiya Musokotwane: You didn’t have very militarized colonial experience as was the case elsewhere in Kenya or in South Africa. So the British were very white glove here. I think part of that is Zambia was never really seen as a place where they were going to settle…it was seen as a resource country.

Tamara Winter: The British occupied what they called “Northern Rhodesia” from the late 19th century all the way until 1964. After gaining freedom Zambia began to function as a democracy. However, within a decade of independence the country was under one-party rule.

Mwiya Musokotwane: Seven years later became a single party socialist state, as was the fashion in Africa those days, and you know that was basically the beginning of a long and steady decline for the country.

Tamara Winter: The economy was soon in crisis and actually contracted for decades.

Mwiya Musokotwane: We ended up losing three to four times our GDP per capita over the 20 years of socialism that we experienced. And then people basically got to a point where they had enough and demanded liberal democracy again.

Tamara Winter: After a series of coup attempts…

Archived audio: Where the rebel officers had attempted to announce they had attempted to overthrow the government because it was corrupt.

Tamara Winter: …and internal struggles in the 90s, that saw former leaders imprisoned…

Archived audio

Kenneth Kaunda: Today, God is great indeed. I am out, but I’ve not been told why I was in the prison for five months and seven days.

Tamara Winter: Zambia has once again begun the move towards a multi-party democracy. Just last fall, Hakainde Hichilema, who ran for president six times in the last 15 years, was finally elected.

As recently as 2017, he too spent time in prison, accused of treason for his role in anti-corruption protests against the former president. Now, Hichilema is committed to an ambitious agenda and has already begun traveling, connecting with other world leaders…

Archived audio

Kamala Harris: Well it is my honor and pleasure to welcome you, Mr. President, to the White House.

Tamara Winter: …working to ensure that democracy in Zambia will be bolstered by strong national institutions and a renewed commitment to economic development.

Archived audio

Hakainde Hichilema: For us to be able to run our countries in a manner that would deliver what we may call democratic dividends.

Kamala Harris: That’s right.

Hakainde Hichilema: Delivering accelerated economic growth development to offer opportunities to our people. I think, Vice President, that’s what will sustain democracy. That’s what will make democracy attractive.

Tamara Winter: Hichilema grew up in a farming family and spent years in international business. His presidency promises a new era for Zambia, one focused on economic growth and greater stability in the government.

Mwiya, who was born in the late 80s, grew up watching Zambia’s economic and governance struggles first hand.

Now in his early 30s he wants his investment firm to be an engine of development not just for Zambia, but for all of Africa.

This vision drives Mwiya’s interest in Nkwashi. You can hear the same far-reaching desire when he explains why he wanted to build a city in the first place.

Mwiya Musokotwane: I was asking myself, “how can I apply this to fix these problems as opposed to being a bystander?” I started thinking about the resources I had available to me. It just so happened that my family owned a ranch about a half-hour drive out of Lusaka and it was large enough that something meaningful could be done there.

Tamara Winter: Mwiya mentioned Lusaka.

That’s the capital city of Zambia and the largest city in the country with between two and three million residents. It’s a bit larger than Chicago and slightly smaller than Berlin. And the problems he’s talking about? Well, the city is growing fast—faster than many of its institutions can cope with. As recently as October of last year there were major blackouts across Zambia.

Power isn’t the only element of infrastructure under strain in Lusaka. It’s estimated that by 2030, the city will have a shortage of three million homes.

Part of Mwiya’s drive to build a new city nearby was to add another living and working hub: one that could be a home to professionals and those who want to connect more directly with the rest of the world.

Mwiya Musokotwane: Nkwashi is a satellite town to Lusaka. We like to call it a knowledge city. We’re anchoring the city on institutions of learning and it’s been designed to be able to be a home to up to 100,000 people.

Tamara Winter: Those learning institutions include a 130 acre university campus and the Explorer School which provides entirely online education for primary and secondary school.

Archived audio: Imagine a school without borders. A school where students and teachers come from places all around the world from Bahrain to France, from Australia to Zambia.

Tamara Winter: In Zambia it is common for the children of wealthier families to be educated outside of the country, in Johannesburg or even London, where Mwiya went to school. The Explorer School also reaches across borders with students in Nigeria, India and beyond but is anchored in Nkwashi.

By creating learning institutions in Zambia that are internationally connected, Mwiya hopes there will be even more reason for those seeking economic and educational advancement to stay.

Mwiya Musokotwane: We’re creating these institutions that hopefully can be the engines of initial economic growth. If Explorer School and Explorer Academy are fantastically successful that then creates the natural impetus to create city number two and three and four and five.

Tamara Winter: Large scale new city projects like Nkwashi sit squarely at the intersection of public and private institutions. They are often so significant in scope that they require cooperation from local and national governments, in addition to willing investors. Luckily, Mwiya was prepared to navigate both of those worlds from an early age, whether or not he was fully aware of it.

Mwiya Musokotwane: I didn’t really grow up with a very boxed-in view of the world.

Tamara Winter: His parents made sure of that. His father is actually one of the architects of Zambia’s financial system.

Mwiya Musokotwane: He’s like a super disciplined academic type person and he’s also been a central banker and economist and policy maker. A lot of the conversations he would have would be around things to do with how to develop Zambia. How to develop Africa at large.

Tamara Winter: His mother was an entrepreneur.

Mwiya Musokotwane: She had her own ways of conveying similar values to us. But most of hers were more practical so I think everything I learned about business as an example, I learned from her.

Tamara Winter: Growing up in a household with international business interests meant an early window into the wider world.

Mwiya Musokotwane: I would go with my parents on their trips to figure out different commercial undertakings they might want to get involved in like acquiring land and stuff like that at a super young age. It created this very like, explorer type mindset in me. I think that’s stuck with me into adulthood.

Tamara Winter: But Mwiya was also an introverted kid who preferred his own company. Luckily at home he was in an environment that filled him with a fierce curiosity. His parents nurtured his development—each in their own way.

For example, when he was 13 his father gave him a biography of Albert Einstein. His mother? Well, she gave him The Power of Positive Thinking.

Mwiya Musokotwane: You know, where my dad is taciturn, she’s more expressive. Where his interests lie in more technical facts hers are much more to do with human wellbeing. He’s taught me how to build systems and she’s taught me how to lead those systems.

Tamara Winter: And now, with a project like Nkwashi, Mwiya is combining lessons from both parents.

Mwiya Musokotwane: Building cities and building institutions of learning...it sits right smack on the intersection between public sector and private sector work.

Tamara Winter: These projects also take a hefty dose of confidence and that ‘explorer mindset’ that Mwiya described. Like Patri Friedman and Mark Lutter, Mwiya’s interest in new cities came from his dissatisfaction with the status-quo solutions he saw being offered to the structural problems in Zambia.

Without Mwiya’s imagination, the land that is now becoming Nkwashi could have been put to more mundane use.

Mwiya Musokotwane: There was the possibility of just subdividing allotments and then selling those, but that also felt very boring and like, low-impact. And the possibility of building something more meaningful seemed more interesting. So we’re like, “Okay we’re going to build a city.”

Tamara Winter: In the red dirt and scrub brush, Mwiya saw something possibly transformational that could reach far beyond 3,000 acres outside of Lusaka.

Mwiya Musokotwane: Right now what we have is a situation where Africans regardless of where they live in the world are treated as nominal equals. It’s one thing to be equal in the law, it’s another to be equal in the way someone regards you in their hearts. And I think that’s what places like Nkwashi represent for me.

Tamara Winter: Mwyia’s clear sense of purpose in building Nkwashi is not always as easy to detect in the world of new cities. Nor is the seamless mix of public and private.

That intersection can sometimes be an uncomfortable one. Remember, when Paul Romer proposed the notion of charter cities, he was clear: they would be special opportunity zones run by other governments. That idea met with almost instant backlash.

Isabelle Simpson: The argument is that Paul Romer’s model was too neocolonial because he would have these foreign countries come and intervene, but that when it’s private entrepreneurs because they are not bound to a particular country that it’s not neocolonial.

Tamara Winter: Isabelle Simpson is a PhD candidate at McGill University studying new cities and startup societies.

Isabelle Simpson: But obviously from the perspective of the local people it is very much neocolonialism.

Tamara Winter: Discomfort over foreign governments running cities in other countries is part of what spurred changes in how new cities are discussed and planned.

Patri Friedman of Pronomos Capital—who we heard from earlier—is especially interested in thinking of new models for charter city development.

Patri Friedman: That idea that a charter city is operated by a foreign power that just didn’t fly at all. So today’s charter cities are overseen by the host country and often are public private partnerships with companies that will build and operate the city.

Tamara Winter: But this model presents challenges of its own.

Patri Friedman: The gold standard right now is the Honduran ZEDE system.

Tamara Winter: In Honduras, laws were passed to seed the ground for new city developments.

Archived audio: Honduras has began to create two of the twelve regions of development and employment also known as charter cities.

Tamara Winter: Called the ZEDE laws, they were so controversial they created a constitutional crisis, and inspired multiple protest movements.

Local suspicion towards new city projects has been common in Honduras.

One project, Prospera, has had ongoing tensions with the population that lives near its borders.

Prospera has also been criticized for its legal system. A board of seven arbiters, many of them not native to Honduras, oversee private disputes in the city. They are asked to make rulings over residents who may or may not speak English and who are governed by a code that has borrowed liberally from different existing sets of laws.

That’s a pretty extreme example. Mark Lutter, the director of the Charter Cities Institute, who you heard from at the beginning of the podcast, has been critical of this particular aspect of Prospera.

Champions of new cities do, however, speak glowingly about the possibilities of these kinds of mix-and-match legal systems, ones that allow laws to be switched out and updated like software. From Patri Friedman.

Patri Friedman: What’s interesting to me from an infrastructure perspective is that modifying other kinds of infrastructure—power systems or sewer systems of a city—is very, very difficult but law is a virtual layer so it can be modified the same way you deploy new software builds.

Tamara Winter: And the sources for these new software builds? They can come from almost anywhere.

Patri Friedman: It’s a really, really interesting point of leverage to say can we essentially write better operating systems or copy the existing operating systems, that is, copy functional sets of laws and administrative procedures from countries that work well and bring them to other countries.

Tamara Winter: To critics of the new city movement this description of governance sounds too straightforward. It is emblematic of the tendency of charter city advocates to oversimplify complex issues. Isabelle Simpson goes all the way back to the first moments of Paul Romer’s original TED talk as an example.

Isabelle Simpson: He begins this talk by showing an Associated Press photo of African students who are sitting under streetlights at an airport and they’re sort of bent over their textbooks.

Archived audio

Paul Romer: Take a look at this picture. It poses a very fascinating puzzle for us.

Isabelle Simpson: So already I find this sort of annoying because people have this really bad habit when they want to illustrate dysfunction or chaos they use Africa.

Archived audio

Paul Romer: These African students are doing their homework under streetlights at the airport in the capital city because they don’t have any electricity at home.

Isabelle Simpson: And Romer does not mention that the students are from the Republic of Guinea and the airport is the international airport there. And the year is 2007.

Archived audio

Paul Romer: Let’s just pick one, for example the one in the green shirt.

Isabelle Simpson: Romer then gives one of the students a fictive name, “We’re going to name him Nelson.”

Archived audio

Paul Romer: Nelson.

Isabelle Simpson: I bet Nelson has a cellphone.

Archived audio

Paul Romer: I’ll bet Nelson has a cellphone. So here’s the puzzle. Why is it that Nelson has access to a cutting edge technology like the cell phone, but doesn’t have access to a 100 year old technology for generating electric light in the home? Now in a word the answer is rules. Bad rules can prevent the kind of win-win solution that’s available when people can bring new technologies in and make them available to someone like Nelson.

Isabelle Simpson: Actually the causes of electricity blackouts here are complex and a comprehensive explanation would have required Romer to address in addition to the poor tariff structures—what he says are the ‘bad rules’—he would have had to talk about the country’s weak infrastructure, issues of transmission and distribution losses, supply shortages and lack of diversity in the electricity generation mix, corruption distorting contract negotiation, and the neocolonial economic situation that thrives on extraction by foreign companies which are the ones grabbing the most electricity at the lowest price.

All these complex elements, they don’t fit into Romer’s narrative about bad rules.

Tamara Winter: The reason scholars like Simpson fear this simplification is because simple-sounding problems invite simple solutions that overlook necessary complexities.

Isabelle Simpson: If you say that you want to build a new city what is it exactly that you mean by city? Isn’t a city a political space where people with different opinions and different ambitions will come and debate and sort of try to create this better society all the time? Or are you trying to create this community of like-minded people which ultimately is just sort of a gated community?

Tamara Winter: In addition to political questions about new cities, there are also cultural and historical ones. Juan Du is the author of The Shenzhen Experiment: The Story of China’s Instant City. She’s also…

Juan Du: …the Dean of the Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design at the University of Toronto.

Tamara Winter: In her book, she pushes back on the popular narrative about Shenzhen: that until 1979 it was a sparsely populated backwater. And after government investment and its designation as a special economic zone only then did its population and economic output explode.

Juan Du: I think it’s important to keep in mind what accounted for Shenzhen’s rapid population growth wasn’t necessarily just top-down policy, it was a bottom-up willingness that people wanted to go there.

Tamara Winter: In her book, Du unpacks how Shenzhen’s history allowed it to rapidly transform into the megacity it is today.

Juan Du: The centuries of history prior to 1979 is as important as the history of the last four decades. The incredible urbanization and economic growth in Shenzhen was built up on foundations that was already preexisting and those foundations took decades if not millennium to be built.

Tamara Winter: Du also takes issue with many of the popular statistics about Shenzhen pre-1979 that feed the city-built-from-scratch narrative.

Juan Du: People think that in 1979 it was just a small sleeping fishing village of 30,000. First of all, there are no villages that have 30,000, especially a sleepy one and a small one at that. Shenzhen was a conglomerate of 2,000 villages and several historic townships that existed for centuries.

Tamara Winter: The population of that 2,000 village conglomerate? Closer to 300,000. And it was this preexisting network that ushered contemporary Shenzhen into being.

Juan Du: There are so much local and indigenous knowledge and organizations and economies and local networks and international networks of those local indigenous villages that formed and actually allowed Shenzhen to survive its most difficult start up period at the first five years, the first ten years.

Tamara Winter: The willingness in the new city world to downplay this part of Shenzhen’s story in favor of a more a-historical, top-down narrative worries Du.

Juan Du: City making is a very, very complex and difficult process. The misconception that Shenzhen grew from scratch that it was a blank slate or a tabula rasa is, I think, the most dangerous misconception. That one can take zero, one can take a blank sheet of paper and that all you need to do is add money and policy that you can have a city.

Tamara Winter: But looking at some proposed new city projects it seems like that’s exactly what certain investors hope to do.

In 2020, Hong Kong real estate developer Ivan Ko proposed a creatively named new city “Nextpolis” to be located in Ireland and populated by residents of Hong Kong who wanted to escape that city’s increasingly challenging political environment.

There was also a proposal in Singapore for a floating city that could house migrant workers and move, when needed, to be near construction projects.

These simple-sounding solutions point to other important questions that need to be addressed in the new city ecosystem. Like who has a say in governance. Simpson points out that many of the cities cited as examples of new city developments—Shenzhen, Dubai, Singapore—are also those with restrictive, even authoritarian, national governments.

Isabelle Simpson: It’s very bizarre that charter cities entrepreneurs would use this very authoritarian model as their blueprint for this sort of pro-free market, pro-freedom, individual freedom developments that they’re trying to do.

Tamara Winter: One of the most high profile new city projects currently under construction— Saudi Arabia’s NEOM—fits this mold.

Archived audio: The contemporary city needs a full redesign. What if we removed cars? What if we got rid of streets? What if we innovated in the public space?

Tamara Winter: Backed by hundreds of billions of dollars of government money, this ambitious plan includes everything from automated ports, to city modules spread out over hundreds of miles of desert and connected by high-speed rail. Promotional materials make it sound almost irresistible. As one Wall Street Journal article put it: it’s Disneyland meets Dubai.

Archived audio: Through advanced manufacturing methods we will create green industries of the future with sustainability and reusability built into their DNA. Because any business destined to change the world, must also protect it.

Tamara Winter: NEOM is part of Saudi Vision 2030, the flagship project of the authoritarian Saudi government of Muhammed bin Salman. It has ruthlessly targeted journalists, activists, and critics at home and abroad.

Isabelle Simpson: Entrepreneurs who are very insistent on freedom of association, freedom of movement, freedom of speech. Their model for charter cities are authoritarian countries.

Tamara Winter: Nkwashi, however, is not this kind of project. It’s being built in Zambia by someone with deep roots in the country. And it is being supported by a new administration that is committed to using economic development to build more democratic institutions.

Some form of government support is crucial in creating a new city. The projects that succeed will have both government support and a significant connection to the place where they are being built.

Nkwashi has that connection. Even the name of the city speaks to its Zambian roots.

Mwiya Musokotwane: It means eagle and so the Zambian national bird is the fish eagle and so we decided to name the city after the national bird and we chose to name it in a language that was indigenous to the area.

Tamara Winter: However, these close ties don’t mean the city and the ideas that come along with it will be instantly adopted.

Mwiya Musokotwane: I think people think of us as being fairly forward-thinking and maybe a little bit crazy sometimes, but I think in a good way.

Tamara Winter: Some might view Nkwashi as ‘crazy’ but that hasn’t really harmed its popularity.

Mwiya Musokotwane: And you know we sold out in like three months; that initial batch of I think 80 five-acre plots, it was.

Tamara Winter: And Mwiya firmly believes in the mission behind Nkwashi—not just the city, but what it could represent.

Mwiya Musokotwane: I see Nkwashi as a beta, as a proof of concept. Speaking as an African, I think one of the challenges Africa has had is we haven’t yet done really big interesting things as a continent—the kind of things where people look at them and say, “Oh wow that’s like super cool that has a lot of positive impact not just for Africa but for the world at large.”

Tamara Winter: That drive to change perception is a personal one for Mwiya, shaped by experiences he had during his university years in London. At 17, he left Zambia, hopeful and a bit apprehensive.

Tamara Winter: He made friends quickly and found community in the classroom. However, while in London he also experienced everyday racism. This might not sound that revelatory—a young African man encountering racism in early 2000s London.

What makes these experiences so important is the way Mwiya talks about them.

Mwiya Musokotwane: Running in the train station to catch the train and then policemen in the train station stop you like, “Where are you running to?” I’m in a train station, it’s obvious I’m going to catch a train. You know, it’s interactions like that where I felt like I was nominally equal.

Tamara Winter: Did you catch that? Nominally equal. Mwiya uses the same words talking about these incidents as he does when describing the necessity of Nkwashi. If Nkwashi is proof of concept and other similar new cities can be built around Africa, Mwiya hopes that—in time—through the educational and institutional development they bring, the international perception of Africa and Africans can change.

In the end, there are as many questions about the future of new cities now as there were twelve years ago when Romer gave his talk. Maybe even more since there are real projects being launched. I was once a die-hard evangelist for new cities, a true believer. I still see the promise in the model, but now I approach the subject with more humility. Basically I’m trying to remember how little I know about what the next decades of new city development will entail.

The world of new cities is shifting all the time. There have been some major changes just in the last few weeks. Remember the ZEDE laws in Honduras? They don’t even exist any more! They were unanimously repealed by Honduras’ national congress.

I’m still optimistic that some version of new cities will fit into the fabric of solutions to economic challenges. But I also recognize that, in 30 years, the actual model or models that succeed may look very different from many of the projects that have been proposed so far.

In the meantime, knowing there are people like Mwiya out there, thoughtful enough to meaningfully consider the big questions facing their societies and daring enough to work on audacious solutions, gives me a lot of hope.

Beneath the Surface is a production of Stripe Press. The senior producers for this series are myself and Everett Katigbak. This episode was produced by Jack Rossiter-Munley. Whitney Chen was our production manager. Our sound mixer and sound designer was Jim McKee and we had editing support from Astrid Landon. Original music for this episode was composed by Auribus.

Visit press.stripe.com to learn more about Stripe Press.

That’s it for this episode. I’ve been your host Tamara Winter. This is Beneath the Surface.

Episode 01 B-side

Interview with Juan Du

Tamara Winter: Welcome to Beneath the Surface B-sides where we bring you full interviews with infrastructure experts. If you listened to the first episode of this podcast you heard excerpts from my interview with Juan Du. She is the Dean of the Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design at the University of Toronto and the author of The Shenzhen Experiment: The Story of China’s Instant City.

In our conversation she offers insights into Shenzhen’s history, explains the personal connection to the city that inspired her to spend 15 years writing a book about it, and reveals why she thinks the ‘Shenzhen Experiment,’ as she calls it, is far from over. So without further ado, here is a lightly edited version of my conversation with Dean Juan Du.

Tamara Winter: So we’ll start with the hardest question first. Tell me your name, your academic affiliations, and why I’m talking to you right now.

Juan Du: The why I’m not sure if I can tell you! So, hello, my name is Juan Du, I am the Dean of the Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design at the University of Toronto in Canada. And I recently relocated in the last six months from Hong Kong to Toronto. So it’s nice to be speaking with you.

Tamara Winter: And tell me, so you’re an architect by trade. I would love if you could tell me a little bit about your background. How did you end up writing this book? Because, well you know certainly Shenzhen’s architecture is mentioned, that isn’t really the defining feature of the book. And maybe you could tell folks what the name of your book is as well.

Juan Du: Sure. So the book is called The Shenzhen Experiment: The Story of China’s Instant City and the book as it was published is probably the fifth evolution of it or reincarnation of it. I didn’t start out by writing such a book because I am trained in architecture. And I started out to write a more architectural book about the city and specifically about the urban villages of the city. However, as I started to uncover more and more about the urban villages, I discovered a larger story really at the story of the city and the story of China. It is a story that I think is very misunderstood. It essentially is the story of China in the last 40 years and how that is contextualized within a broader understanding of the history of China, perhaps over a few centuries. So it just became a much bigger book, perhaps not in length, but in scope, the more I researched and worked on that.

One of the first reasons why I wanted to write the book is actually based in my first hand experience of planning and design projects in Shenzhen. And I came across this deep history and vibrant, overlooked, urban neighborhoods that is not present in the way that Shenzhen is typically portrayed in either national media in China and especially international media in the world. It’s usually portrayed as the city without history, the city without any important pre-urbanization culture or people of significance. And that was just very much contrary to what my own experiences and later my own research uncovered. So this is why I decided to take on this challenge of writing this book. And it was very difficult for me, precisely because I wasn’t trained particularly to write such an expansive book, but it was very much a learning journey. And with these knowledge and lessons that I’ve uncovered over a decade of research and writing, I think it does contribute back to my own discipline of architecture and urban planning and design, but also I hope it contributes to others who are interested in economics, politics, geography, environmental transformation, whether it is in the Chinese context or anywhere else in the world.

Tamara Winter: For anyone who isn’t familiar, what is Shenzhen? Where is it? And maybe you can answer this now, or I can ask it again in just a little bit, why is Shenzhen such a significant city?

Juan Du: Sure. I’ll start with the ‘where’ first, maybe. So Shenzhen is located in southern China. It’s at the southern east most tip of China, just north of a river from Hong Kong. And the river is called the Shenzhen River. And this river is the border between the city of Shenzhen and the city of Hong Kong. And it used to also be an international border that you know defined between China and colonial era Hong Kong, which was ruled by the British. So it is a very interesting location. I would also say that what’s a unique geographical feature, in addition to where it’s located, is the people via one fact: it is the only city in China’s southern region where the primary dialogue is not Cantonese, which is the southern dialogue of China. The primary dialogue in Shenzhen is Mandarin, which is a typically northern dialogue that people have used to speak everywhere in China.

So this is not to say that Shenzhen is a northern city, but it really testifies to the cosmopolitan nature of the city, that it is located in the southern tip. And it has a very rich southern history of China, but it is a city of migrants from all across China. And it’s really, I would say the most diverse city in China in terms of the backgrounds of people and where they’re from geographically and perhaps also socioeconomically. And I think that for me, is what makes it a significant city. And I would say that it also makes Shenzhen the most dynamic city in China today because of that mixture, because of that diversity. And it has this extreme mixture of low tech and high tech industries, it has this extreme mixture of urban and rural cultures. It has this extreme mixture of kind of the very local regional quality of a southern city with international enterprises and international headquarters via where it is and its unique history.

It’s also significant if we want to speak about numbers, it’s also significant in terms of its population number. It is a city of 20 million people, which makes it a rare mega city in the world, 20 million. But what makes it more unique is that in the 1970s, the population in Shenzhen was 300,000. So it went from 300,000 to 10 million in two decades. And then when it was 10 million in the early 2000s, everyone said, “Well, this is it. This must be it. I mean, Shenzhen has reached this potential. It’s no longer unique. It’s no longer special.” Yet, over the following decade and two decades, it continued to grow into where it is today, a city, 20 million people. And that makes it an internationally significant city because that type of population growth, not only is it unprecedented in China, it’s unprecedented in the world, anywhere, at any moment of history, in the world.

Tamara Winter: I really appreciate that because you just flagged Shenzhen’s population in the '70s. I’m going to come back and ask you a question about that because when I was working at the Charter Cities Institute, I was under the impression that the population was actually 30,000, but there’s a very particular reason why you used the 300,000 number.

Juan Du: Yeah.

Tamara Winter: But there were a lot of people who speak as though Shenzhen’s history began in 1979. Why was 1979 such a significant year for China more broadly?

Juan Du: Right. So 1979 is a very significant year for both Shenzhen and China. In 1979 was the year, the city of Shenzhen was established, meaning it was formally designated as an urban unit. So prior to 1979, the region was called Bao’an county, which was a rural county in the province of Guangdong. So in 1979, it was designated on this special entity as a city of Shenzhen, but the further significance of 1979 to both Shenzhen and China is because 1979 was the year China, via the central government in Beijing, launched China’s reform and opening. It was basically the beginning of a series of economic and sociopolitical reforms that entirely pivoted China’s economy and culture onto the world stage and into the identity of what China is today, internationally.

I think for anyone who perhaps do not have that particular memory or anyone who’s younger than 50, I would imagine that they would be very shocked if they’re shown images or facts about what China was like in the 1960s and '70s, including anyone who’s younger than 50 in China today. The year 1979 to launch, it was a very pivotal moment and pivotal year. It’s not to say everything was instant.1979 launched the reform and opening. 1979 established the city of Shenzhen, but the first decade of that was very rocky. It was very difficult. It was very challenging. Shenzhen was very close to being shut down multiple times, reform opening policies was close to shut down multiple times. It wasn’t until the mid 1990s, right, almost two decades after 1979, did it stabilize and the country and the city had enough confidence that this is definitely the right direction for the city and for the country.

Tamara Winter: And for anybody who doesn’t already know, how did allowing Shenzhen, designating it as a special economic zone, change the city? I mean, you’ve alluded now to population growth. I’m also curious about GDP growth and more broadly how Shenzhen’s success really impacted the whole country.

Juan Du: In 1979, what was initiated was not only the city of Shenzhen, there also was initiated a policy to create special economic zones. And in 1979, Shenzhen was one of four special economic zones that was created. So what makes Shenzhen’s beginning as a city unique is that within that year, it was both a city and a special economic zone in China. There are many conversations about special economic zones. It continued to be used almost like a miracle growth formula in the world today, especially in developing economies and cities, what it meant for China at that time for Shenzhen, at that time by special economic zone, it simply meant within the designated special economic zone of Shenzhen, which was only actually the southern half of the city of Shenzhen.

But within that special economic zone that the zone and the city government had the power to create an experiment with various policies and various mechanisms that was not legal, that was not allowed and not existent outside of the zone. And I also think sociopolitical reforms and policies that were experimented with, that at the time was not possible anywhere else in China. For example, at that time, if you were not born in a particular city and had its local residency status, which is called Hukou in China, you cannot legally work in anywhere but that city. You cannot get a job, you cannot get housing, you cannot get married anywhere else, but that city. It was very much mechanism of economic and population management system in China, let’s say, that it was a planned economy. But because Shenzhen was designated as a special economic zone, in Shenzhen if you were a migrant from somewhere else, from another city, from a rural region, from a village, you could get a job.

You could go to school, you could rent a home, you could get married, you could make so many decisions about your own life that at the time in China, you couldn’t. And that’s why it was significant. And I would say, that’s what attracted people to go there. So what makes it unique, it’s not only the number and the population growth. I think the question is that why did all these people go there? That’s one of the biggest, I think overlooked lessons. Shenzhen as is being discussed either as a charter city precedent or model, or as a special economic zone model. I think it’s important to keep in mind, is that what accounted for Shenzhen’s rapid population growth wasn’t necessarily just top down policy. It was a bottom up willingness that people wanted to go there.

People were not forced to go there. People were not sent to go there. People left the comfort of their home. People left the comfort of their jobs and their families to go to, at the time, I said the first decade was very difficult for Shenzhen, but people left the comfort of their home. And under a planned economy, if you had a job, you had that job for life. It may not be a job you love, but you had it. You had housing, you had a job, you had your basic social networks. Within those first decade, the type of people that the city attracted were a very unique type of people. It was people who was more adventurous, it was people who is entrepreneurial. It was people who are not satisfied with what life offered them in wherever they were. So what makes Shenzhen a really interesting case study for me is a much more closer understanding of what propels people, what would attract someone to whichever place or whichever socioeconomic costs are coming from.

What would attract someone to leave everything they know, and go to this place and believe that it is a land and opportunity. And to the testament of Shenzhen, even though there has been, of course, many people who arrived in Shenzhen and couldn’t make it and left, but many more did stay, right? The fact that it started with the population 300,000, now it’s 20 million. We’re basically talking about 20 million migrants, 20 million people, because it’s only within four decades, right? New population growth. Those were born in Shenzhen is still not the majority of the 20 million. The majority of the 20 million are migrants from everywhere else. They went to Shenzhen and they were able to, despite whatever challenges of a new environment, changing policy, they were able to take root and take advantage of the various unique opportunities that the city have offered and was able to make their homes there.

Tamara Winter: You went to Shenzhen, I believe in 2005, I love that the book kind of starts and ends in the same place. Forgive me if I say this wrong, in Baishizhou, what did you see when you first got to Shenzhen and why is that specific village so significant to you?

Juan Du: I did use Baishizhou, a particular urban village, as a historical site and device to open the book and end the book. And there are personal reasons. And I think for me also intellectual reasons to want to do that. Personal reasons is that in 2005, I was working in Beijing at the time and I was flying to Shenzhen to work. And I would fly to Shenzhen once every week or every two weeks. I’d fly in in the morning and I’d leave in the last flight out, because why would I want to stay in Shenzhen, it’s a city with no history, no culture. I’m only going there on business. And then one day my meeting ran over, the city official, the urban planner that I became very good friends with decades later was driving a bit too slow, going to the airport. And I missed my flight.

So the city put me up in a hotel. It was a place called Overseas Chinese Town, O-C-T, which is the nicest neighborhood in Shenzhen. It has these kind of Italian villas. It has a very famous theme park. It has these tree-lined streets and some business hotels. So I was put there to stay for the night and take my first flight out the next morning. And in the hotel room, I couldn’t sleep. So I thought maybe a walk would do it. So I started walking and got lost and walked into this incredible scene, this was probably past midnight already, of a city square with everyone full of people at midnight, full of people, cooking and eating and this outdoor market, lots of kids running around. And I described it as seeing, I think in my book rather cinematically, but it was a very cinematic experience.

It was as if I discovered this new world that no one had told me about, none of the architects and planners and government officials I had met at that time in Shenzhen, because I was just starting to understand the city has ever mentioned such a place of urban villages. None of what I’ve read about the city have talked about it. So it was just this incredible thing. And then later I was to understand that Baishizhou is the city’s largest and most populous urban village. It has this incredible history that I speak about in the book, I think in one of the chapters. And I did decide to end, I believe it was the last chapter on Baishizhou as well to, in some ways to talk about what started out as a very touristic understanding of what the urban village is and what the city is.

But after a decade and a half of researching and interacting and learning from the local residents and the local scholars, I start to really have a much deeper understanding. However, by, at the end of the 15 years, Baishizhou was in the process of being cleared out for demolition. So I really wanted to be able to include that part in the book to really put in some ways a sense of urgency to what I wanted to call out to attention of both the people in Shenzhen, people in China, people everywhere else is that very often what’s happening through an urbanization process of so-called urban renewal, what we are demolishing, which on the surface might cosmetically look as if it shouldn’t be there, that in fact is the very heart and engine of what made that city vibrant and important in the first place. And that, for me, I think has a certain degree of urgency and has a degree of importance to be able to share with an international audience.

Tamara Winter: Your book does, I think a masterful job of pointing out many misconceptions that people have about Shenzhen, whether it’s that Shenzhen’s success should primarily be attributed to top down government, to the idea that Shenzhen before the city kind of grew to become what we know it to be today, had no one there and it was just kind of this like back woods village and the land was pretty insignificant. So I’m wondering if you could tell me what are maybe some of the sort of most jarring misconceptions that people have about Shenzhen and why was it so important to you to kind of take pains to correct them?

Juan Du: The reason why it’s important for me to put that front and center is because I had those very same misperceptions and misconceptions of the city when I started first going there. But what’s different between myself and perhaps the greater media perhaps is that my misconceptions are very quickly dispelled by me understanding the city more, but then is to watch that those misconceptions, not only did it stay throughout the decade and half I was researching and writing the book, they actually grew, it grew in their status. And it grew in the number of people who held them, it was primarily at first just kind of a national discussion. And then it became an international, Shenzhen became an international model city.

And with Shenzhen’s reputation rising in the last decade, the misconceptions also arose in their importance and impact. So I thought it was really important to outline that and to say that this is why I’m writing the book, is I wanted people to have an understanding that not only is Shenzhen not the way that is commonly being perceived. In fact, it is the exact opposite. That’s what I think is really intriguing and unfortunate to me about these misconceptions of Shenzhen, and there’s many. But I think for the purpose for the book and for the purpose of me trying to create it more succinctly and communicate them, I had outlined that there was misconceptions of time, misconceptions of people, misconceptions of purpose. So misconceptions of time, we spoke about the fact that Shenzhen was established as a city in 1979. And for the most part, we’ve been speaking about the city’s growth in the past four decades and how that paralleled or instigates, actually, the growth of China in terms of economics in the past four decades.

However, if you have read my book, you understand that in the book, I take pains to research and create evidence to show that the centuries of history prior to 1979 is as important as the history of the last four decades. And that if we did not understand what had happened in Shenzhen in the region in China prior to 1979, there could be no understanding of why Shenzhen was created. Why there was this special economic zone. Why China launched the reform opening. And most importantly, I think I wanted to evidence and I hope it was compelling to anyone who has read the book that the incredible urbanization and economic growth in Shenzhen in the past four decades absolutely was built up on foundations that was already preexistent in the region. And those foundations took decades, if not millennium, to be built.

And that if Shenzhen was what people think it was in 1979, and this is where the misconception at place is also one of the misconception is that people think that in 1979, it was just a small sleeping fishing village of 30,000. First of all, there are no villages that has 30,000, especially a sleepy one and small one at that. But Shenzhen was not a small sleeping fishing village. Even if we don’t look at the population statistics, Shenzhen was a conglomerate of 2,000 villages and several historic townships that existed for centuries. And this is really important to understand the region and this particular place, the people, the geography, the fact that it was a port, the fact that it had these rivers, the fact that it had all of this land, that was cultivated.

So that geographic understanding is really important because the misconception that Shenzhen grew from scratch, that it was a blank slate or tabula rasa is I think the most dangerous misconception that one can take zero, one can take a blank sheet of paper and that all you need to do is add money and policy that you can have a city. So I think that really is the biggest and most dangerous misconception of Shenzhen because that’s not how it happened. And the reason why I say it’s the most dangerous misconception is that Shenzhen now has been used as a model city in the context of charter cities, in the context of new cities, in the context of special economic zones, to demonstrate that not only is it possible to grow a city from blank, to plan a city from nothing. And all you had to do is add foreign direct investment.

Not only is it not that, it’s the opposite of that. There was so much local indigenous knowledge and organizations and economies and local networks and international networks of those local indigenous villages that formed and actually allowed Shenzhen to survive its most difficult start up period at the first five years, the first 10 years. And this is really something that I’m very passionate about to advocate because I believe in the importance of cities, I even believe in charter cities as something that’s important to talk about, I believe that we can make new cities and make it livable and attractive, but we also need to understand that it’s not just add money or just add policy, there is no miracle growth in this way that it is city making. It’s a very, very complex and difficult process.

And if my study of Shenzhen hopefully can evidence is that it’s really important to understand that preexisting geography of people, history, culture of that place and that we should see those existing geographies, not as something to get rid of, not as a inconvenience, not as a nuisance, but really see them as the key ingredient, the seeds, if you will, that can contribute to the success of the future new city or the future new charter city.

Tamara Winter: I think a lesser understood part of Shenzhen’s kind of contribution to the world, its cultural contributions. There’s a music video that you reference. This is around the time that you’re starting to get the first music videos coming out of China and these music videos are being shot literally as the city is being constructed. And one thing you’ve taken quite a lot of care to sort of show, not tell people about, and whether it’s in your book or in your appearances since then, is the real spirit of the people in Shenzhen.

Juan Du: Yeah. So, I think in the book, I say one evidence, the first master plan of Shenzhen was based on a anticipation of a population 1 million by 2010. And by all accounts, that was a very ambitious master plan. There are not many cities that was able to go from scratch to 1 million. It was already a very ambitious plan, top down planning, many cities who’s been planned to have city of 1 million do not have any, right. There are many ghost towns, whether in China or elsewhere, more top down planned cities fail than succeed. So the top down planning from policy, from resources, infrastructure, housing, central funding, what have you, anticipated population of 1 million by 2010. The actual population in 2010 in Shenzhen was 10 million, 10 times more than what was planned via policy and the various instruments of that, whether economic or spatial. So 90% was unanticipated bottom up, right? 90% was just, people wanted to go there.

And this is where the importance of the urban village I was speaking about earlier because the city was planned with its infrastructure, whether it’s housing, schools, hospitals, restaurants, to serve a particular proportion of the population. Who made up for the 90%? The local communities, the local villages, they turned their own houses into rental housing. And then once they had rental housing, the new migrants opened up restaurants. So what’s interesting of Baishizhou is that you can walk into any street in Baishizhou, and you can, within one hour, sample food from all over China, because they’re all opened by migrants from all over China. So this is what I mean by that I think we have underestimated the powers of bottom up action and bottom up growth. And because the book is intended for a general intellectual audience, I do not put too much academic or theoretical terms in there, but that aligns with my own work, in understanding informal urbanization, informal settlements, and to understand how communities build their own housing, build their own economy, build their own social network and social systems.

And I’ve come to really understand that for a city to be a healthy, vibrant, expanding city, you need both formal or top down policy and planning and governance. It’s not just, that’s not important. It’s very important without that 10%, right? Without that top down, there would’ve been no Shenzhen. But this other part, the informal growth, the informal settlements, kind of these informal networks that very much is tied into and contributed to that formal economy, that formal policy, you need that without the informal on the bottom up, there would be no Shenzhen as we understand it today, and we would not be speaking about it and I would not have written a book and it would not be cited in India and Africa, Honduras, Ireland, wherever it is around the world as a model city, right? Because that top down aspect, that kind of planning aspect is actually quite standard, but it’s this kind of how these policies, when emerged with the local population of the preexisting villages and were emerged with all of these people from all around the country, coming into this one city and all collectively believing in the possibility of the new.

That is an incredible, I think, a social, psychological experiment. So, I go back to why I called my book The Shenzhen Experiment is because I think that it is very much an experimental city. It was set up as an experiment for China to experiment with, can you have market economy in a communist country? But I think its significance goes way beyond that. It’s an experimental city in understanding human nature. It’s an experimental city in understanding both the incredible opportunities of urbanization and rapid growth, but also the native impacts on the environment on the geography of rapid urbanization. You know, the fact that it’s the state of where it is today, of being say a mega city of between 10 million to 20 million people, it’s only in the last two decades. That makes it one of the world’s youngest cities and newest experiments.

I think in the conclusion of my book, I said, “I think the Shenzhen experiment’s far from over.” So I am always very uncomfortable, even myself to make any very declarative or conclusive comments about Shenzhen, because I think we don’t really understand it yet. Despite the fact that I’ve spent these time researching into it and reading everything I can about Shenzhen and southern China, I think there’s still so many more we don’t know about the city. There’s so much more lessons to uncover. So I think this experiment continues and where the city is today and where it’s going to go, it’s an open question. It’s an absolute open question. So for me, is that there’s so much for us to learn about this city and for the knowledge and experience of the city to benefit both cities and governance and also individuals in China, in Asia, but also I think there’s a lot of lessons to offer to people from all around the world, whether they’re decision makers or they’re citizens themselves.

In the book, I do highlight a number of individuals I have met. Some of them are historical figures, and some of them are common everyday people and how their own lives were impacted by the urbanization of the city. But also I wanted to show how they, as individuals contributed to the city and ultimately shaped the city. And one thing I always like to remind myself and remind everyone else, that 20 million sounds like a monolith block. It’s very common for when, especially in the American context, when we look at Chinese cities or when we look at China, we see these huge gigantic numbers and that just automatically turns apart your brain into thinking that is monolith. But I do want to highlight that it’s 20 million of individuals and it’s 20 million individuals not unlike you and I. It’s 20 million individuals who have their strengths and weaknesses, who have their own neuroses, who have their emotional baggage.

And these individuals, whether they’re mayors or they’re construction workers, they have had and continue to have influences in shaping the city and that’s whether it’s in Shenzhen or elsewhere. And that ultimately is something that I really would like for, especially the English reading audience and especially the North American audience, to have a more humanistic understanding of Shenzhen, to have a more humanistic understanding of China, to have a more humanistic understanding of cities that in one country or in one city, there are so many diverse views and so many different diverse entities and that individuals, nationalities, places of residence should not be grouped in within one overarching understanding about one particular country. Imagine if that be the case in the reverse, right.

Do we, as individuals, want to be defined by the overall message that came out of the U.S in the past five years? I would think not. So in the same way, I would also ask everyone to have the curiosity, to try to understand whether it’s China or India or Africa or France, to understand the nuances of these political situations, and to understand the difference between national politics and individual rights and individual dreams.

Tamara Winter: Beneath the Surface is a production of Stripe Press. The senior producers for this series are myself and Everett Katigbak. This episode was produced by Jack Rossiter-Munley. Whitney Chen was our production manager. Our associate producer and editor for this episode was Astrid Landon. Our sound mixer and sound designer was Jim McKee. Original music for this episode was composed by Auribus. To learn more about Stripe Press, our books, our films, and more, visit press.stripe.com.

That’s it for this B-side. I’ve been your host Tamara Winter. This is Beneath the Surface B-sides.

Episode 02

Salton Sea: White Gold in the California Desert

Tamara Winter: Earlier this year I visited California’s Salton Sea for the first time. I went with my friend and colleague Everett Katigbak. He’s a producer on this podcast, and you’ll hear from him throughout this episode. It was his first trip back in over 20 years.

Everett Katigbak: It just surprised me how little has changed. But also seeing the lake itself was kind of surprising. When I was standing there the other day, it’s a no man’s land. It’s literally scenes out of Mad Max. I know we say that kind of jokingly, but you can really envision it.

Tamara Winter: Since the waters of the Colorado River rushed into the Salton Basin in 1905, the lake they created has been a source of promise and conflict. Now it’s shrinking, and has become one of the most polluted bodies of water in the country.

It’s also poised to become one of the largest sources of lithium in the United States. As the world transitions from gas to electric vehicles, demand for lithium is increasing rapidly. And so is interest in the Salton Sea. The potential for investment and industry could be transformational for the area.

But what will that transformation look like? What impact will lithium extraction have on local communities? And what can examining the history of the Salton Sea reveal about its present and future?

Hello and welcome to Beneath the Surface, a podcast from Stripe Press all about new ideas and big questions in the world of infrastructure. I’m your host Tamara Winter.

In the first episode of Beneath the Surface we looked at charter cities. New urban developments built almost from scratch through financial investment and political will. In this episode we’re visiting a very different kind of place.

Everett Katigbak: So we’re here in Salton City. This is, I think the largest community out here around the Salton Sea.

Tamara Winter: The communities that have grown near the Salton Sea are unincorporated. And include everything from off-the-grid artist communities to half-inhabited suburban developments.

The fate of these communities is tied to the sea. When it was a tourist destination they felt the benefits. But that opportunity has long since dried up, along with the sea. Now, the promise of becoming a ‘lithium valley’ is bringing a wave of development that could breathe new life into the area.

I mentioned my colleague Everett. Well, when we started talking about doing an episode on the history and future of Salton Sea, we found out that Everett and his family have a stake in the area. At the tail end of the Salton Sea’s resort era, his family bought some land there. Hoping, like many, that it was an up-and-coming oasis.

Everett Katigbak: This is the place where when I was young my parents actually bought a plot of land. We’re literally standing on this plot of land. Around it there’s a handful of homes, but for the most part it’s a bunch of empty lots out here. It is a very picturesque view. It’s like a postcard. But I imagine the closer you get to it the less photogenic it gets.

Tamara Winter: You have a daughter Drew. How do you hope she experiences the Salton Sea? Do you think in her lifetime it might get, I don’t know, poppin’?

Everett Katigbak: I don’t know…I don’t imagine she’ll have any connection to it. I never talked about it growing up. It’s just something I totally forgot about. The more my parents are getting older and thinking they need to let go of this place the more I’m hearing about the lithium stuff. So for me it’s something that I kind of want to hold onto for a little longer and see if something happens.

Tamara Winter: In the early 20th century, major construction projects were underway across southern California. Engineers planned irrigation canal networks to bring water to arid corners of the California desert. The dream at the time was to provide water for farming to the scorching hot Imperial Valley where temperatures regularly spike well above 100 degrees. Rain rarely falls. And snow has been recorded only once in the last century.

But nature had other plans.

For millennia, the Colorado River had occasionally made its way into the Salton Basin, creating lakes. But in the spring and summer of 1905 multiple floods wore down and eventually broke through the canal gates. And water poured into the basin.

Initial attempts to close off the flow of water failed miserably. Another flood in November swept away the hastily constructed dams of gravel and brush.

For two years the water flowed. And for two years crews worked around the clock. In sweltering temperatures. Under the threat of multi million-gallon flash floods. To redirect the river. When the water was finally stopped, the newly formed Salton Sea covered over 400 square miles.

The early years of the Sea were mostly quiet.

Naturalists categorized the many species of birds that began to congregate on its shores. The Salton Sea Wildlife Refuge was created.

During the Second World War the sea became a source for fish when German u-boats made the ocean too dangerous. The military used the sea for bombing exercises. In fact, the crew that dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima flew practice missions over the Salton Sea.

The sea, however, was already shrinking and becoming saltier and saltier. But this didn’t stop interest in the sea from growing during the postwar economic boom.

One of the people who moved to the Salton Sea after World War II was Helen Burns. She and her family made their home on a small plot of land owned by her father. Her daughter Donna Kennedy—who was barely more than a toddler at the time—remembers those early years well.

Donna Kennedy: She moved us down to the Salton Sea into a trailer which had an adjacent outhouse. And we had a standpipe where we could stand and bathe. It didn’t make any difference that we were nude because no one else was there, it was completely deserted, just us.

Tamara Winter: Living in the semi-wild meant Donna and her sister had a unique childhood.

Donna Kennedy: We did a lot of swimming in the sea, it was very clean then. Sandy beach and very lovely. So my sister and I would just frolic in the water and the sagebrush and try to catch lizards and avoid snakes and scorpions too, we didn’t care for scorpions.

Tamara Winter: Helen, however, had big dreams. She set up a makeshift stand built out of a piano box and some palm fronds. Truck drivers. Immigrants trekking up from Mexico. Occasional tourists. They all stopped by Helen’s for soda, coffee, postcards, or tubes of Salton Sea sand.

Business grew. And so did the number of tourists. The Salton Sea became a destination, marketed as an inland resort—the next Palm Springs.

By the 1950s the Salton Sea was the place to be. And Helen expanded to meet the demand.

Donna Kennedy: Basically if you wanted to have some fun you went to Helen’s. At her high point she had a marina, a boat dock, gas tanks. A campground. Besides the bar and restaurant, the motel, but I’d say by 1958 things were really moving.

On 4th of July she had hell divers and people water skied across the sea and back and got trophies and wore little horns. On New Years she had icebreakers and people skied across and back. There was the Miss Salton Sea Contest, the Mr. Salton Sea Contest. There were treasure trails where people went across the desert in their dune buggies and they’d try to find all the treasures she had hidden…it was just roaring with activity.

Tamara Winter: Helen even earned a new title: Queen of the Salton Sea.Helen wasn’t the only one who saw the promise of the sea in the 50s and 60s. Other entrepreneurs, sensing opportunity, hitched their fortunes to the sea. The newly formed Salton City grew and grew. Promotional videos from the time show a desert oasis, a paradise of crystalline waters and inviting beaches. The future for Salton Sea couldn’t have looked brighter.

Archived audio: In an article appearing in the The Los Angeles Times April 17th, 1966, Salton City was chosen by a group of planners, architects, administrative officers, politicians, professors, and associated thinkers as one of the 24 major cities in southern California in the year 2000.

Tamara Winter: By the late 1960s and early 1970s however, tourism was drying up. And so was the sea. The water level dropped so significantly and the salt level rose so much, environmental observers worried that the fish and birds that lived in and around the sea would begin to die.

The lack of rainfall in the Imperial Valley meant that the sea’s main source of new water was agricultural runoff. Which brought with it pesticides. Soon birds began dying and algae bloomed in the once clear waters. Resorts closed or scraped by with reduced clientele. When powerful tropical storms ripped through the Imperial Valley in the mid-70s many packed up for good.

Archived audio:

Whacko: It used to be a real nice dinner house owned by Bill and Maxine McClaren.

Huell Howser: What happened to it?

Whacko: Eh, the floods.

Huell Howser: Uh huh.

Whacko: They kinda split up, well, actually it’s the floods what did it.

Tamara Winter: By 2000, Salton City was far from being one of southern California’s major cities as the LA Times had predicted. In fact, its population shrank to less than 1,000.